Marshall is one of the world's top experts on network business models and platform. It was my special pleasure to have this in-depth discussion.

How to define platforms and how they are different from ecosystems

How do you define platforms and ecosystems?

Personally, I don't think platforms and ecosystems are identical. But I think there's a fairly straightforward way to position a platform.

Platform

I like to define a platform as an open architecture with rules of governance to facilitate interactions.

The open architecture is what allows third parties to participate on the platform.

The rules of governance are what invites them in and tell them how to create value.

And then the transactions would actually create value, whether you're consuming a ride, or a tweet or a video or things of that sort.

I really think of it as those three components, the open architecture, the rules of governance, and the interactions.

Ecosystem

Distinguishing that from the ecosystem, I like to think of the platform partners as the ones that do abide by the rules of the platform, but the ecosystem can be broader and include competitors that don't necessarily abide by the rules of the platform.

So that encompasses another additional layer or wrinkle. So hopefully that clarifies at least how I like to think between platforms and ecosystems.

I'd like to think of the platform partners as the ones that do abide by the rules of the platform, but the ecosystem can be broader and include competitors that don't necessarily abide by the rules of the platform.

3 tests to determine whether your business can become a platform or should it participate in someone else's platform.

You recently presented a framework on how companies should think on whether they should create platforms themselves, or should participate in someone else's platform. I think this is something that a lot of people are interested and also struggle.

There were three tests that help you determine whether you can be the platform.

1. Inverted Firm Test

The first of these is really a test that we like to call the Inverted Firm Test. Which is how much of the value can be created outside versus created inside? If it's easy for third parties to create that value, then the market will tip to the platform. And it's only a question of who's going to be that platform, the market will tip toward a platform.

For example, for Airbnb or Uber or Facebook, a lot of the value is being created by third parties that offer the rides, the rooms, or the posts or things like that. So is it easy for third parties to create value and for the firm to tip from inside to outside production?

2. Critical mass test

The second test is, do you have critical mass to tip that market? Do you have the resources, in this case to secure drivers or secure folks for your social network or hosts for your rooms?

There's a fair amount of resources that are needed to achieve the critical mass so the consumers are picking your platform, as opposed to the alternative.

3. Can you control the relationship?

The third test is really whether or not you're close to the interface. Can you control the relationship?

If you have to reach through someone else's platform in order to control the relationship or facilitate the interactions, then you're going to have to partner with someone else. You can't actually do that control.

To give you an illustration of it, Apple in some sense reached through the systems of AT&T when it introduced the iPhone. And it took control of the AT&T relationship with its user. It became more tightly related, or tied to the iPhone than to the AT&T telecommunications network.

Assess your test results

So again:

Can the market tip, can you move it toward an inverted firm?

Do you have the resources to tip it?

And can you control the relationship?

And if that's the case, then yes, you should.

If you fail to answer one or two of those questions then maybe you're going to need to partner with someone else that either has the resources or has the relationship. So in some sense, you do become a federated platform.

And if that test also fails, if you can't form a federation to do it, then you may be doomed to be a product on someone else's platform. So it creates a kind of decision tree or structure that helps you figure out where your position in the market might be.

Shift to a new architectural form, that's as important today as the rise of the industrial firm a hundred years ago.

Let me ask you a little bit broader question. Your book "Platform Revolution" was quite insightful and it was published at the time when the term platform started to become prominent (2016). But in a broader sense, why has this trend became so prominent? Is it because of the Ubers of the world?

I actually think is that transition's been happening for a little bit longer than people realize. In some sense, we've been studying platform-like business models since the turn of the century, when the dot-com boom and the dot-com bust. Geoff Parker and I, for example, did some of our thesis work around the free information goods when companies were running up and Marc Andreessen was building Netscape, and Microsoft was battling the Internet browser wars. All those things had been around for a little bit of a while.

But I actually think it's a combination of two main factors as to why we're seeing more of them now than in the past.

The first oneis what I think everyone's already recognized in the transactions costs, which information technology reduced so much that it's easy to coordinate activities and reach people, and search and find. So it's really easy to conduct your actions in the marketplace.

The one that I think is missed is the extent to which platforms internalize externalities, or they internalize network effects.

I'll give you an example. Your Google search makes my Google search better. Or maybe my movie watching behavior makes your movie watching experience better. What happened is that Google, and Netflix, and Amazon, and others take this information, these positive spillover benefits, and they manage them for a large ecosystem. They can spread that value over large numbers of different users. That's not something individuals can do for themselves. So I couldn't make my own search better based on your search behavior or learn from your movies.

You need someone to orchestrate that tiny bit of positive externality, which is why you come back to a platform, with a governance model to handle those spillovers. And so as transaction costs have fallen, it's allowed large scale aggregation of small scale network effects, that wasn't possible before. So you start to internalize this spillover benefit, which leads to a completely new organizational form. We referred to it earlier as this inverted firm, where you go from production inside the organization to production outside the organization. And you're using information and spillover benefits for that to happen.

I actually do think that there are structural changes in the economy happening alongside this. And actually we are literally witnessing the emergence of a different structural architectural form, that's as important today as the rise of the industrial firm a hundred years ago.

Now, if you give me one extra moment, I actually do think that there are structural changes in the economy happening alongside this. And actually we are literally witnessing the emergence of a different structural architecture or architectural form, that's as important today as the rise of the industrial firm a hundred years ago.

Supply side economies of scale

If you take a look at what happened a hundred years ago, with supply side economies of scale - you got massive railroads, you got oil and gas companies, you got auto manufacturers. All of these are driven by massive supply side economies of scale. It's high fixed cost, low marginal cost. Scale gives you volume, volume lets you drop price, and your competitors are out of the market.

Demand side economies of scale

That's not what's happening here. Network effects are also called demand side economies of scale. What's happening is, as you get a marketplace that attracts users, they create value for one another, which attracts more users, which creates value, which attracts more users. So what's happening is you're pushing the demand curve out, rather the supply curve down. You're operating on the revenue or value side of the equation, as distinct from operating on the supply, or cost side of the equation.

You're operating on the revenue or value side of the equation, as distinct from operating on the supply, or cost side of the equation.

That's a fundamentally different organizational form then what we've observed previously. Again, it's these inverted firms, values being created by users outside and their creating value for one another.

Second degree network effects and how to increase platform stickiness

The network effect seems to become a concept that many people start to understand, but you've taken it one step further with one of your recent papers, where you try to differentiate between different types of network effects. Could you share more about it?

A lot of people think of network effects in a static sense. So the network tends to increase in value as you attach more people to it, or riders attract drivers, so attract riders to attract drivers. But they tend not to think about the intertemporal effect. So what we get in our most recent research is to actually look at, not only how much those network effects attract in a given moment of time, but how much of it is sticky and attract users in the next period.

We've actually explained behaviors such as Groupon, which should have network effects. It should have merchants attracting consumers, attracting merchants, attracting consumers. But the problem is they're not sticky. They're not getting the benefits into the next, into the future periods in the way that Google, or Amazon, or Apple are getting it. People are sticking around into the next periods. And we could find at least a couple of factors that are contributing to this. You might meet on Groupon a merchant, you might try a haircut or an oil change, or order a pizza in that case. But you don't go back. Your next interaction will be direct with a merchant as opposed to through Groupon. Well, then you've lost the relationship and you're not able to use that data, to create additional value for other users.

Now contrast that with a similar firm, by the name of Meituan in China. It started two years later than Groupon, but they did some things that were really clever.

One, they handled the order systems and the logistics systems. So what this means is that not only if you try to get a pizza from a restaurant, they will handle the delivery. Meituan even got to the extent when they'll actually handle the supplies to the restaurant. Well, now you've got both ends of the transaction, and it stays. So the next time you order, you order again through Meituan, as opposed to going directly to the restaurant. It's much, much stickier, in this case.

They also then captured these high frequency interactions that you might get. So you might order food, you know, every couple of weeks, which isn't necessarily a high-margin business, but then they add on these infrequent interactions, things that are high value. For example, they started adding on travel, hotel, and reservations for vacations. That might happen every once a year, but they used the high-frequency engagement to then layer on another value-adding interaction. They were so successful, they stole the market effectively from Ctrip that had been the leader in travel in China.

they use one network effect, to layer on another network effect, both through time, and then adding more valuable network effects in other areas. We use the design of these network effects that will help you persist through time, and layer on additional value to create sticky ecosystems.

So they use one network effect, to layer on another network effect, both through time, and then adding more valuable network effects in other areas. We use the design of these network effects that will help you persist through time, and layer on additional value to create sticky ecosystems. For what it's worth, people might order a couple of times on Groupon. They order 26 times a year from Meituan. It's more than five times as valuable, you know; in a sense of ecosystem, it's a really different ecosystem. So you need to figure out how to get these network effects to persist over time. For those that are interested, the academic papers there, we'll have to have a practitioner's version of that paper sometime soon.

Focus on technology and strategy first before marketing

It's a very interesting and fascinating study. Companies from China or Singapore like Grab and Meituan like you mentioned, they figured out a way to make their products very sticky, and could retain users because of that. And I think what you just mentioned is also very interesting, is about how do you find a use case with high frequency, and then overlay others, maybe lower frequency on top of it. Why do you think companies in the West are doing this less successfully?

You have to be careful - some of it is by accident, some of it is by design. It is the case that there were half a dozen different other companies at least in China, all fighting for that market. And it happens to have been Meituan that succeeded. So we have to be a little careful about kind of a post hoc ergo propter hoc - they were the ones that won, that did it, now let's figure out what really distinguished them from the others.

I do think it's essential to pull back and actually ask, "How do you design network effects? How do you design stickiness? How do you capture that relationship?"

I do think it's essential to pull back and actually ask, "How do you design network effects? How do you design stickiness? How do you capture that relationship?"

I do think also that some in the West had been thinking perhaps more on the marketing side. It's one thing to actually pull users in, and in fact, Groupon had been pretty good at that. But if it's not sticky, the problem is you're pulling the users into a leaky bucket. And you're far better off designing network effects first, then designing a marketing campaign. So maybe it's an emphasis, I'm a technologist at heart.

I actually think you need to focus on the technology as strategy and design from the ground up, as opposed to starting from the marketing, and picking the technologies in afterthought. I think technology is fundamental to the strategy. You start there with the design questions, and add the marketing later.

Why breaking up big tech is a bad idea

Staying on the topic of network effect, there are a lot of conversations about breaking up big tech companies. You showed a very elegant graph on how using network effect equation you can decide whether or not it makes sense to break up tech. Can you share a bit more of that?

Very happy to do that. So I'll see, if so best is to do this graphically, but I'll see if I can do this with words, because it's tough to do that with equations. But let me see if I can anchor the intuition.

One of the questions in antitrust is "are these firms so big that we would all be better off in a more competitive environment, where there are more firms competing with one another to create value?" My honest answer is, I think that particular approach is a bad one.

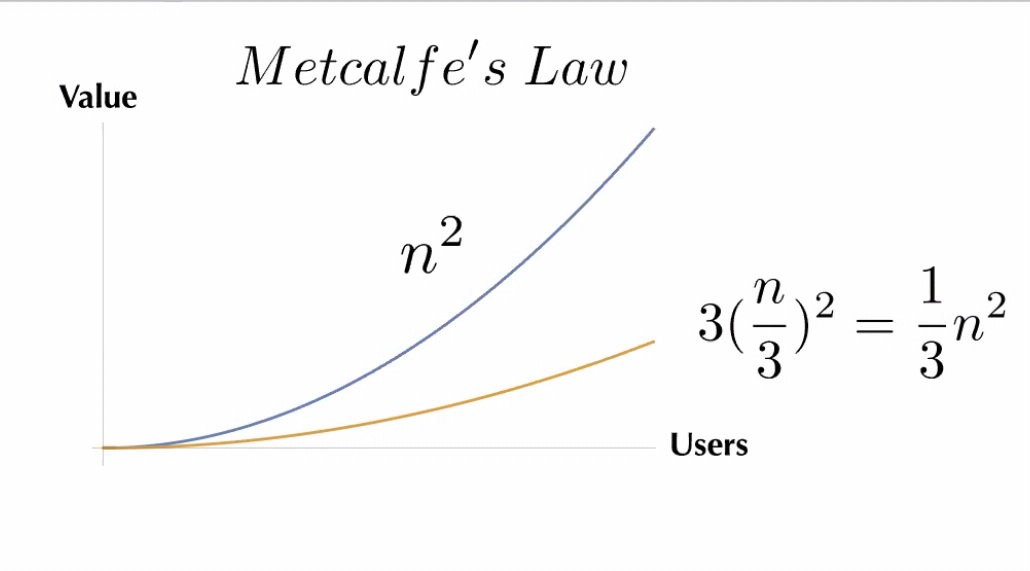

And there's a very simple reason. Almost all these firms are characterized by what everyone recognizes as Metcalfe's law. We all recognize Metcalfe's law rises exponentially or proportional to N squared. Now think about the follow-up. What happens if you were to split one of these major firms into three separate companies? You take Facebook and split it into Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram, unraveling those three firms.

Well, then you take one-third over N, you square it, you get one-ninth, multiply it back by three, because you've got three companies, but you've only got one-third the value. So you've got an N squared not going up like this, but going up like this [less steep], and you're not getting the benefits of the network effects. You're spreading value over smaller pools of users, which is a bad idea. Breakup isn't the right way to ask a question. So it wasn't competition, we should've focused on, it's creating value that we should've focused on. So that brings us to a different question.

Breakup isn't the right way to ask a question. So it wasn't competition, we should've focused on, it's creating value that we should've focused on.

I do think that some of these firms have exercised market dominance in some bad ways, that they're in fact, misbehaving. We get fake news. We get some of these firms being both the umpire and the player on their own, in the same game. That's not fair. That really isn't fair to other ecosystem partners. But we need to do this in a way, that's going to change the behavior and still create the value.

One possible solution is analogous to what the Europeans did with PSD2, where the Payment Services Directive 2 in Europe. That allows users to designate to third-party companies, open APIs, giving other companies the ability to access their data, with their permission to create new value. So imagine that you had the permission to open your APIs on Facebook. And Google or Amazon could go in and create value on your behalf. So, you could open your Amazon account, and maybe Facebook can then add additional networks. Or Google could correct the privacy policies on Facebook by giving you new options. You gain control by opening the APIs, but third parties can come in and then add them, even startups that don't necessarily have all that starting data, could gain access via the APIs as a way to come in and attach the add value. I think that's a healthier way to start doing this, because what it does is it creates competition on top to create adding value, rather than splitting these apart, which divides value. I think that an open system is a more healthy approach.

How platforms will evolve in the next several years

It's a fascinating subject for a long discussion, but I definitely agree with you. Thank you for explaining this in a very clear and elegant way. Talking about platforms, where do you see platforms evolving in the next several years?

My answer to that is I believe very similar to the observation earlier. I do believe that this is a structural shift, in the organization of production. And I'm going to claim that I think the platform type firm is now going to be with us effectively indefinitely. In the same way as the supply side of the economy of scale has also come in the industrial era, had also come to be with us indefinitely. It is structurally so powerful, and it is so good at creating value relative to other mechanisms, that it's going to be there for a very, very long time.

My suspicion is also, again because I think breakup alone is not a great idea, that you're going to see larger and larger ecosystems competing with one another. But I think one of the correct regulatory mediation mechanisms is to have platforms compete with one another to create value. Even as there are large ones that we have to put other governance mechanisms in place to make the welfare distribution fairer. And put it slightly differently, there's another line of research that we're working on which I would call a Magna Carta of Citizen's Rights. At the moment, you and I don't get votes in the chiefdoms of Page, Bezos, and Zuckerberg. It would really be nice, if we did get a vote in those policies. And I actually think we need to have other mechanisms in place that give consumers and the participants in these ecosystems ways of guiding and influencing those policies, and not just participating with the take it or leave it set of terms.

I do think platforms are going to be with us for a really long time. We're going to see them compete with one another. And I do think we're going to need new mechanisms to actually provide more citizen rights in these ecosystems.

I do think there's a little bit of history that's kind of interesting. You saw the rise of industrial firms misbehave a lot when they first got started. Industrialized, terrible pollution. There were also terrible with labor practices. We're seeing that same thing. We're seeing fake news, as information pollution. We're seeing not sharing the value with hosts, and drivers, and others. You're not getting rewarded for your Facebook posts, in the same way. We will see regulation restore a little bit more balance over time. I think there's some great lessons from history. So I do think platforms are going to be with us for a really long time. We're going to see them compete with one another. And I do think we're going to need new mechanisms to actually provide more citizen rights in these ecosystems in setting policy.

So it seems to be early days, and because it's early days, government is just catching up on platforms.

Policy makers are not as fast with the technology as the industrialists. That's just a fact. And so we need to figure out new mechanisms to help deal with that.

Anticipate major platform transitions in the B2B space

People very well understand what is happening in B2C. Everyone used Uber and eBay and what have you. But then a lot of things are starting to happen in B2B. Can you share on a high level, what is a trend in B2B? Because you see the entire picture.

Anticipate lots of transitions in the B2B space. It's absolutely the case that most of the initial use cases are in the B2C space, but do expect to see much, much more in the B2B space. There are a few fundamental differences worth highlighting.

Almost all these things should focus at the interactions level. Again, going back to definition, it's the open architecture and rules of governance that facilitate interactions. That's where the value is created. That's the consumption of the ride, the tweet or whatever. But you can think of it as the value of an interaction, versus the volume of an interaction. So the value of an individual search is trivial, but there are trillions of it. But the value of an Uber ride is much higher, but there are lot fewer of them. In B2B versus B2C, the value is even higher, but the transactions are even smaller. The trick is to design network effects that cover these interactions that are high value, but fewer in number.

It's absolutely the case that most of the initial use cases are in the B2C space, but do expect to see much, much more in the B2B space.

Another element of this is you need to be much smarter about ongoing processes. In case of B2C, it may be a one-time consumption fact. It may be a ride, or a tweet, a stay, and you're in and you're done. For B2B, you may have to be a project that is managed over a period of time. Great examples are Salesforce or SAP doing something where you may need multiple ecosystem partners. You need to manage coopetition more for your ecosystem partners to create value.

SAP is a great example. Many independent software vendors might compete with one another. How do you get them to share code, share ideas? SAP does these wonderful SAP developer networks, which reward them with reputations for having shared ideas. And there's even empirical evidence that shows that participating in those makes each of the ecosystem partners more productive. It's more important to orchestrate the value across these ecosystem partners.

Again, go back to the test. Is it possible for third parties to create value? The answer is yes, the industries will transform. We should expect to see this in industries that have a high proportion of information.

Healthcare, for example, will absolutely transform, a huge amount of the value is in information.

Finance is also going to transform in there. You know, so we're starting to work, for example with Siemens in health.

We're starting to work with them in rail and transport, and some others.

My colleague, Geoff Parker is starting to work with Shell Oil on the huge process of de-carbonization and how do you bring ecosystem partners and to cause these entire ecosystem industries to shift.

So how does that actually work? B2B is a different space. It's more complex. We saw, for example, that GE did not get it right in Predix. The idea is a good one, but the implementation was not correct. They tried to boil the ocean. They weren't designing network effects. They weren't starting niche and going broad. There are a whole bunch of strategies you should employ to do it the right way. Short is, do expect to see it. It's going to happen. You need to be careful about the design. You can do it the right way in order to actually get the benefits for the long-term.

Rise of platform talent

We have many MBAs following us. And you also recently did a research on platform talent, and it seems that there's an opportunity to become one of the professionals who work with platforms and leverage this trend. Can you share your findings, please?

I have to give fair credit to Peter Evans, who's a colleague on this, who really did most of the work on this study. This is the labor 2020 study on the rise of platform talent.

There are a couple of interesting things.

1. The number of job postings with platform related skills is exploding.

One is the number of job postings. And what we did is to scrape a number of websites, different job websites. The number of job postings with platform related skills is exploding. A huge number of industries are now actively trying to hire platform talent. And candidly, there are not a lot of places actually developing these, because it requires both technology skills, and then also regulatory economic skills.

I'm happy to say at Boston University we actually are trying to teach some of these things. My colleague, Geoff Parker at Dartmouth, is also teaching some of these things. So we're actually trying to provide classes on thinking about network effects, thinking about externalities, thinking about strategy in that context. And also the technology, the APIs, the modularity, the access, as well.

What we also find in the study is that there's a cascade effect. The existing incumbents, in order to become platforms are stealing talent from the existing platform firms. Right, where do you get it? Well, we've already done it. They then are trying to backfill by stealing from one another, and then also hiring from places such as our program, people that are trained in this. And so we're seeing an interesting cascade in different places.

There's also a fair amount of entrepreneurial activity in the launching of platforms, and those are quite interesting. In some sense, I do think younger generations are more aware of platform thinking, as distinct from product thinking. We can have third parties involved in creating the value, and not just doing it all yourself. But I do think that there are some generational differences in how one thinks about the labor in hiring. So we're seeing it in cascading effects through multiple firms and multiple generations.

How to educate yourself about platforms

If I were a student going through a graduate program or a university program, where would you advise me to educate myself on this subject? I mean, apart from following you.

There are very few programs that focus on platforms. To be candid, there is Boston University, there's Dartmouth, Annabelle Gawer teaches some in London. There are some colleagues down in Georgia Tech, a few at Northeastern. It's really not very many places teaching platforms, specifically.

By the way, there is one free course [Platform Strategy for Business] that I offer on edX. It's entirely free. And it teaches just about half of the book. And you can just take that and get a certificate, and get some of the basics. So that's available, just go to edX.org and search [Platform Strategy for Business] in the menu. And then you can get it and it's free.

If you want to cobble together some courses from an existing curriculum, what you would need to do would actually get some computer science, so that you understand modularity and open architecture. You would also need externality economics. So how do you deal with positive externalities and negative externalities? Those tend to be fairly advanced courses in industrial organization that help with that.

platforms are really good at getting people you don't know to give you ideas you don't have. How do you do that? You use mechanism design.

I would also strongly recommend a class that covers information asymmetry. How do you make decisions about questions you don't know? To put it differently, platforms are really good at getting people you don't know to give you ideas you don't have. How do you do that? You use mechanism design. And that's a branch of economics from information economics and principal-agency theory, that you'd need to put together. So you'd need some industrial organization, some information economics, and then do computer science. And those things together, is what you would need to put the training together.

Marshall it has been a really amazing interview. I look forward to following you and channeling your knowledge to the broader audience. And hope we all meet virtually or personally here in London or in the US sometime soon. Thank you so much.

Absolutely, I'd like that. Thank you so much for your interest. It's a great topic.

Notes and mentions

Follow Marshall @ LinkedIn, Twitter

Platform Revolution: How Networked Markets Are Transforming the Economy and How to Make Them Work for You by Geoffrey G. Parker, Marshall W. Van Alstyne, Sangeet Paul Choudary

How Users Drive Value: Platform Investments that Matter| SSRN

What’s happening now — and next — in platform hiring | about Platform Talent 2020 study by MIT Sloan School of Management

Latest Insights & Analysis

We help our clients to define customer-centric strategies that stimulate innovation and create value